Executive Insights

- Weather is the short-term state of the atmosphere, driven by the Sun’s unequal heating of the Earth.

- The six main elements of weather are temperature, atmospheric pressure, wind, humidity, precipitation, and cloudiness.

- The Coriolis effect, caused by Earth’s rotation, dictates the movement of storms and global wind patterns.

- Modern forecasting relies on a combination of satellite data, Doppler radar, and AI-enhanced supercomputer models.

- Climate change is intensifying weather events, making storms wetter and heatwaves longer.

Weather dictates our daily choices, from the clothes we wear to the food we grow. Yet, beneath the simple question of “Will it rain today?” lies a complex interplay of physics, thermodynamics, and fluid dynamics. In the realm of meteorology, weather is defined as the state of the atmosphere at a specific place and time regarding heat, dryness, sunshine, wind, rain, etc. Unlike climate, which represents long-term patterns, weather is the immediate, often volatile, expression of our planet’s atmosphere trying to equalize energy imbalances.

As we navigate the mid-2020s, understanding weather has never been more critical. With the rise of AI-driven forecasting and the increasing frequency of extreme meteorological events, the gap between simple observation and complex prediction is closing. This guide explores the fundamental mechanisms driving Earth’s weather, the modern tools used to predict it, and the distinction between daily fluctuations and long-term climate shifts.

The Fundamental Elements of Weather

Weather is not a single entity but a composite of several measurable atmospheric variables. Meteorologists track these elements to understand current conditions and predict future changes. The interaction between these variables creates the diverse weather phenomena we experience.

| Element | Description | Measurement Tool | Impact on Weather |

|---|---|---|---|

| Temperature | A measure of the kinetic energy of air molecules. It determines how hot or cold the atmosphere is. | Thermometer | Drives evaporation and air density changes, leading to wind and precipitation. |

| Atmospheric Pressure | The weight of the air above a given point. Also known as barometric pressure. | Barometer | High pressure usually brings fair weather; low pressure brings storms and clouds. |

| Humidity | The amount of water vapor present in the air. | Hygrometer | High humidity fuels storm formation; low humidity leads to dry conditions. |

| Wind Speed & Direction | The movement of air caused by differences in atmospheric pressure. | Anemometer / Wind Vane | Transports heat and moisture across the globe; dictates storm paths. |

| Precipitation | Water released from clouds in the form of rain, freezing rain, sleet, snow, or hail. | Rain Gauge | Essential for the water cycle and agriculture; excessive amounts cause flooding. |

| Cloudiness | The fraction of the sky obscured by clouds. | Ceilometer / Satellite | Affects surface temperature by reflecting sunlight or trapping heat. |

The Engine of the Atmosphere: Solar Radiation and Circulation

The primary engine driving Earth’s weather is the Sun. Solar radiation heats the planet unequally, with the equator receiving the most direct energy and the poles receiving the least. This thermal imbalance forces the atmosphere to move, attempting to redistribute heat from the equator toward the poles. This movement creates the global atmospheric circulation patterns known as the Hadley, Ferrel, and Polar cells.

The Role of the Troposphere

Almost all weather phenomena occur in the troposphere, the lowest layer of Earth’s atmosphere extending roughly 8 to 15 kilometers (5 to 9 miles) high. In this layer, temperature generally decreases with altitude. The uneven heating of the Earth’s surface causes air to rise (convection), cool, and condense, forming clouds and precipitation.

The Coriolis Effect

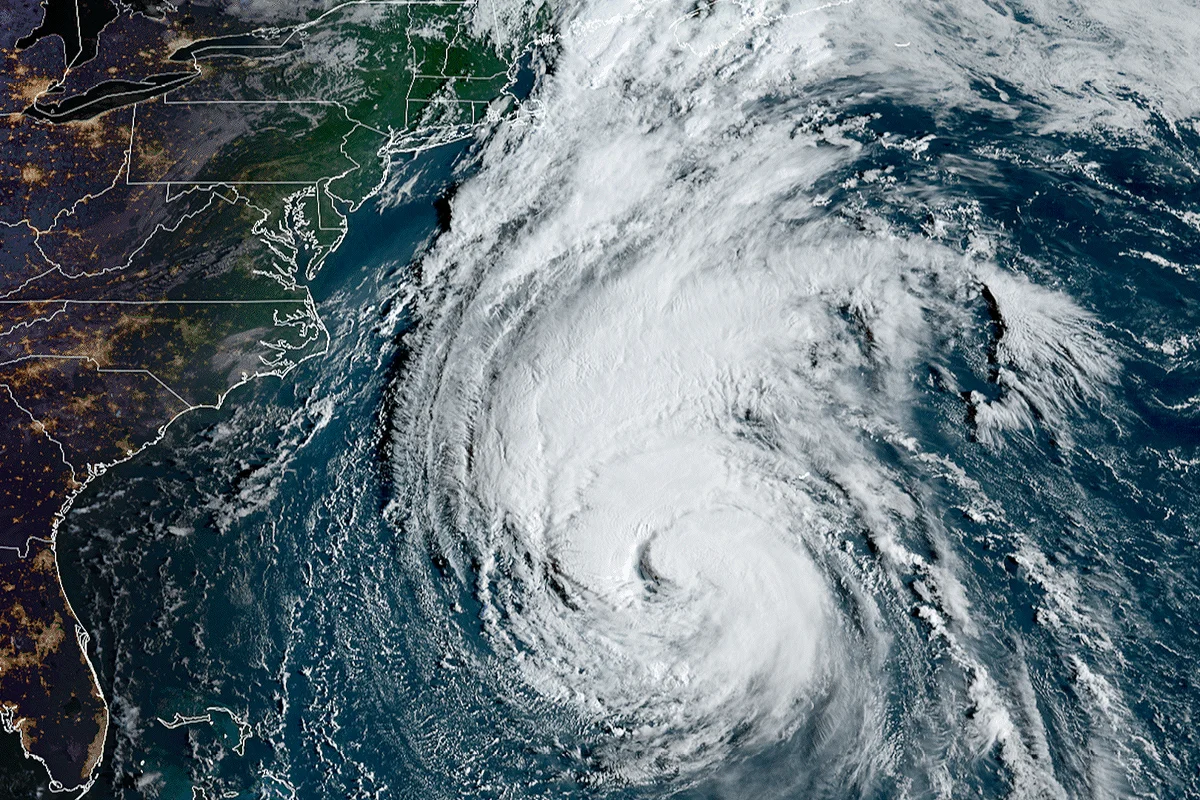

Because Earth rotates, air does not move in a straight line. The Coriolis effect deflects moving air to the right in the Northern Hemisphere and to the left in the Southern Hemisphere. This deflection is responsible for the rotation of large weather systems, such as hurricanes (cyclones) and the distinct spiral patterns seen on satellite imagery.

Weather vs. Climate: A Critical Distinction

While often used interchangeably in casual conversation, “weather” and “climate” represent distinct timescales in meteorology.

- Weather is the short-term state of the atmosphere (minutes to weeks). It is chaotic and difficult to predict beyond 10-14 days. Example: A thunderstorm passing through Chicago on a Tuesday afternoon.

- Climate is the average of weather patterns over a long period (typically 30 years or more). It provides a statistical baseline. Example: Chicago has cold, snowy winters and humid summers.

A helpful analogy is that weather is your mood, while climate is your personality. While a person’s mood can shift rapidly, their personality remains relatively stable over time. However, climate change is currently altering the baseline “personality” of Earth’s weather, leading to more frequent extremes.

Modern Weather Forecasting: From Satellites to AI

The era of looking at the sky to predict rain is long gone. Today, Numerical Weather Prediction (NWP) models ingest billions of data points daily to simulate the atmosphere’s future state.

Data Collection

Forecasting begins with observation. A global network feeds data into supercomputers:

- Geostationary Satellites: Orbiting at the same speed as Earth’s rotation, providing continuous monitoring of specific regions (e.g., GOES-R series).

- Polar Orbiting Satellites: Scanning the entire globe, providing crucial data on temperature and humidity profiles.

- Doppler Radar: detecting precipitation intensity and wind velocity inside storms, crucial for tornado warnings.

- Radiosondes: Weather balloons launched twice daily worldwide to profile the upper atmosphere.

The Rise of AI in Meteorology

By 2026, Artificial Intelligence has revolutionized forecasting. Deep learning models, such as those developed by major tech researchers, now rival or outperform traditional physics-based models (like the GFS or ECMWF) in speed and accuracy for certain tasks. AI models excel at pattern recognition, identifying severe weather setups—such as atmospheric rivers or heat domes—days earlier than conventional methods.

Extreme Weather Phenomena

Weather is not always benign. When atmospheric conditions align violently, extreme weather events occur. Understanding the mechanics of these events is vital for safety and preparedness.

Hurricanes and Typhoons

These are massive tropical cyclones fueled by warm ocean waters (typically above 26.5°C or 80°F). They function as giant heat engines, converting the energy from warm water into powerful winds and torrential rain. The low pressure at the center (the eye) draws air inward, while the Coriolis effect spins it.

Tornadoes

Tornadoes are violently rotating columns of air extending from a thunderstorm to the ground. They usually form within supercells—storms with a rotating updraft called a mesocyclone. Wind shear (change in wind speed/direction with height) is a critical ingredient for tornado formation.

Blizzards and Polar Vortex

Winter storms are driven by the clash of cold polar air and warm moist air. The Polar Vortex is a large area of low pressure and cold air surrounding both of the Earth’s poles. When the jet stream weakens, the vortex can expand or distort, sending frigid Arctic air spilling into mid-latitudes.

The Impact of Climate Change on Weather Patterns

Scientific consensus indicates that anthropogenic climate change is amplifying weather extremes. As the atmosphere warms, it holds more moisture—approximately 7% more for every 1°C of warming (Clausius-Clapeyron relation). This leads to:

- Intensified Precipitation: Heavier downpours and increased flood risks.

- Stronger Hurricanes: Warmer oceans provide more fuel for tropical cyclones, increasing their potential intensity.

- Prolonged Droughts: Higher temperatures increase evaporation rates, drying out soils faster.

- Heatwaves: High-pressure systems (heat domes) are becoming more persistent and hotter.

Conclusion

Weather is a dynamic, powerful force that shapes life on Earth. From the microscopic coalescence of water droplets to the synoptic scale of jet streams, the atmosphere is a system in constant motion. While we cannot control the weather, our ability to understand and predict it has grown exponentially. As we face a future with more volatile atmospheric patterns, the synthesis of traditional meteorology and advanced technology will be our best defense against the elements.

In-Depth Q&A

Q: What is the difference between weather and climate?

Weather refers to short-term atmospheric conditions (rain, sun, wind) happening now or in the near future. Climate refers to the average weather patterns in a specific area over a long period, typically 30 years or more.

Q: What causes the weather to change?

Weather changes are primarily caused by the uneven heating of Earth by the Sun. This temperature disparity creates pressure differences, causing air to move (wind) and moisture to circulate, leading to various weather fronts and systems.

Q: How do meteorologists predict the weather?

Meteorologists use Numerical Weather Prediction (NWP) models that run on supercomputers. These models analyze current data from satellites, radar, weather balloons, and ground stations to simulate future atmospheric conditions. AI is also increasingly used to improve accuracy.

Q: What is atmospheric pressure and why does it matter?

Atmospheric pressure is the weight of the air pressing down on the Earth. It is a key indicator of weather; high pressure generally brings clear skies and calm weather, while low pressure is associated with clouds, wind, and storms.

Q: Why is the weather becoming more extreme?

Climate change is trapping more heat in the atmosphere. A warmer atmosphere can hold more moisture, leading to heavier rainfall and stronger storms. It also alters global air circulation patterns, leading to more persistent heatwaves and droughts.